The complexity of

choice goes further because long-term decisions about technology must also

include implications for long-term recurring costs -- as well as business continuity. As IT architects and operators seek to best map a future

from a VMware hypervisor

and traditional data center architecture, they also need to

consider openness and lock-in.

Our panelists review how public cloud providers and managed service providers (MSPs) are sweetening the deal to

transition to predicable hybrid cloud models. The discussion is designed

to help IT leaders to find the right trade-offs and the best rationale for

making the strategic decisions for their organization's digital

transformation.

The panel consists of David

Grimes, Vice President of Engineering at

Navisite; David Linthicum, Chief Cloud Strategy Officer at Deloitte

Consulting, and Tim Crawford, CIO Strategic Advisor at AVOA. The discussion is moderated by BriefingsDirect's Dana

Gardner, principal analyst at Interarbor

Solutions.

Here are some excerpts:

Gardner: Clearly, over the past decade or two, countless virtual

machines have been spun up to redefine data center operations and

economics. And as server and storage virtualization were growing

dominant, VMware was crowned

-- and continues to remain -- a virtualization market leader. The virtualization

path broadened over time from hypervisor adoption to platform

management, network virtualization, and private cloud models. There have been a

great many good reasons for people to exploit virtualization and adopt

more of a software-defined

data center (SDDC) architecture. And that

brings us to where we are today.

Dominance in virtualization, however, has not translated into an automatic

path from virtualization to a public-private cloud continuum. Now, we are at a

crossroads, specifically for the economics of hybrid cloud models.

Pay-as-you-go consumption models have forced a reckoning on examining your

virtual machine past, present, and future.

My first question to the panel is ... What are you now seeing

as the top drivers for people to reevaluate their enterprise IT

architecture path?

The cloud-migration challenge

Grimes: It's a really good question. As you articulated it, VMware

radically transformed the way we think about deploying and managing IT infrastructure,

but cloud has again redefined all of that. And the things you point out

are exactly what many businesses face today, which is supporting a set of

existing applications that run the business. In most cases they run on very

traditional infrastructure models, but they're looking at what cloud now offers

them in terms of being able to reinvent that application portfolio.

But that's going to be a multiyear journey in most cases. One of

the things that I think about as the next wave of transformation takes

place is how do we enable development in these new models, such as

containers and serverless, and using all of the platform services of the

hyperscale cloud. How do we bring those to the enterprise in a way that

will keep them adjacent to the workloads? Separating off in the

application and the data is very challenging.

Gardner: Dave, organizations would probably have it easier if

they're just going to go from running their on-premises apps to a single public

cloud provider. But more and more, we're quite aware that that's not an easy or

even a possible shift. So, when organizations are thinking about

the hybrid cloud model, and moving from traditional virtualization, what

are some of the drivers to consider for making the right hybrid cloud

model decision, where they can do both on-premises private cloud as well

as public cloud?

Know what you have, know what you need

Linthicum: It really comes down to the profiles of the workloads, the

databases, and the data that you're trying to move. And one of the

things that I tell clients is that cloud is not necessarily something

that's automatic. Typically, they are going to be doing something that may

be even more complex than they have currently. But let's look at

the profiles of the existing workloads and the data -- including security,

governance needs, what you're running, what platforms you need to move to --

and that really kind of dictates which resources we want to put them on.

As an architect, when I look at the resources out there, I see traditional

systems, I see private clouds, virtualization -- such as VMware -- and then

the public cloud providers. And many times, the choice is going to be all four.

And having pragmatic hybrid clouds, which are paired with

traditional systems and private and public clouds -- means multiple clouds

at the same time. And so, this really becomes an analysis in terms of how

you're going to look at the existing as-is state. And the to-be state is

really just a functional matter of what the to-be state should be based on

the business requirements that you see. So, it's a little easier than

I think most people think, but I think the outcome is typically going to

be more expensive and more complex than they originally anticipated.

Gardner: Tim Crawford, do people under-appreciate the complexity of moving

from a highly virtualized on-premises, traditional data center to hybrid

cloud?

Crawford: Yes, absolutely. Dave's right. There are a lot of assumptions

that we take as IT professionals and we bring them to cloud, and then find

that those assumptions kind of fall flat on their face. Many of the myths

and misnomers of cloud start to rear their ugly heads. And that's not to

say that cloud is bad; cloud is great. But we have to be able to use it in

a meaningful way, and that's a very different way than how we've

operated our corporate data centers for the last 20, 30, or 40 years. It's

almost better if we forget what we've learned over the last 20-plus years

and just start anew, so we don't bring forward some of those assumptions.

And I want to touch on something else that I think is really important

here, which has nothing to do with technology but has to do

with organization and culture, and some of the other drivers that go into

why enterprises are leveraging cloud today. And that is that the world is

changing around us. Our customers are changing, the speed in which we have

to respond to demand and need is changing, and our traditional corporate

data center stacks just aren't designed to be able to make those kinds of

shifts.

And so that's why it’s going to be a mix of cloud and corporate

data centers. We're going to be spread

across these different modes like peanut butter in a way. But having the

flexibility, as Dave said, to leverage the right solution for the right

application is really, really important. Cloud presents a new model because our

needs have not been able to be fulfilled in the past.

Gardner: David Grimes, application developers helped drive initial cloud

adoption. These were new apps and workloads of, by, and for the cloud. But

when we go to enterprises that have a large on-premises virtualization legacy --

and are paying high costs as a result -- how frequently are we seeing people

move existing workloads into a cloud, private or public? Is that gaining

traction now?

Lift and shift the workload

Grimes: It absolutely is. That's really been a core part of our business

for a while now, certainly the ability to lift and shift out of the

enterprise data center. As Dave said, the workload is the critical factor.

You always need to understand the workload to know which platform to put

it on. That's a given. With a lot of that existing legacy

application stacks running in traditional infrastructure models, very

often those get lifted and shifted into a like-model -- but in a

hosting provider's data center. That’s because many CIOs have a mandate to

close down enterprise data centers and move to the cloud. But that does,

of course, mean a lot of different things.

You mentioned the push by developers to get into the cloud, and

really that was what I was alluding to in my earlier comments. Such a reinventing

of the enterprise application portfolio has often been led by the

development that takes place within the organization. Then, of course, there

are all of the new capabilities offered by the hyperscale clouds -- all of

them, but notably some of the higher-level services offered by Azure, for

example. You're going to end up in a scenario where you've got workloads

that best fit in the cloud because they're based on the services that are

now natively embodied and delivered as-a-service by those cloud platforms.

But you're going to still have that legacy stack that still

needs to leave the enterprise data center. So, the hybrid models are prevailing,

and I believe will continue to prevail. And that's reflected in Microsoft's

move with Azure Stack, of making much of the Azure platform available to hosting

providers to deliver private Azure in a way that can engage and interact

with the hyperscale Azure cloud. And with that, you can position

the right workloads in the right environment.

Gardner: Now that we're into the era of lift and shift, let's

look at some of the top reasons why. We will ask our audience what their

top reasons are for moving off of legacy environments like VMware. But

first let’s learn more about our panelists. David Grimes, tell us about your

role at Navisite and more about Navisite itself.

Panelist profiles

Grimes: I've been with Navisite for 23

years, really most of my career. As VP of Engineering, I run our product

engineering function. I do a lot of the evangelism for the organization.

Navisite's a part of Spectrum Enterprise, which is the enterprise division of Charter. We deliver voice, video, and data services to the

enterprise client base of Navisite, and also deliver cloud services to

that same base. It's been a very interesting 20-plus years to see the

continued evolution of managed infrastructure delivery models rapidly

accelerating to where we are today.

Gardner: Dave Linthicum, tell us a bit about yourself,

particularly what you're doing now at Deloitte Consulting.

It's been a very interesting 20-plus years to see the continued evolution of managed infrastructure delivery models.

Linthicum: I've been with Deloitte Consulting for six months. I'm

the Chief Cloud Strategy Officer, the thought leadership guy, trying to

figure out where the cloud computing ball is going to be kicked and what

the clients are doing, what's going to be important in the years to come.

Prior to that I was with Cloud Technology Partners. We sold that to Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) last year. I’ve written 13 books. And I do the cloud blog on

InfoWorld, and also do a lot of radio and TV. And the podcast, Dana.

Gardner: Yes, of course. You've been doing that podcast for quite a

while. Tim Crawford, tell us about yourself and AVOA.

Crawford: After spending 20-odd years within the rank and file

of the IT organization, also as a CIO, I bring a unique perspective to

the conversation, especially about transformational organizations. I work

with Fortune 250 companies, many of the Fortune 50 companies, in terms

of their transformation, mostly business transformation. I help them explore how

technology fits into that, but I also help them along their journey in

understanding the difference between the traditional and transformational.

Like Dave, I do a lot of speaking, a fair amount of writing and, of

course, with that comes with travel and meeting a lot of great folks

through my journeys.

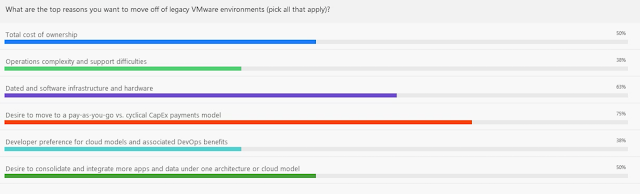

Survey says: It’s economics

Gardner: Let's now look at our first audience survey results. I'd

like to add that this is not scientific. This is really an anecdotal look

at where our particular audience is in terms of their journey. What are

their top reasons for moving off of legacy environments like VMware?

The top reason, at

75 percent, is a desire to move to a pay-as-you-go versus a cyclical CapEx

model. So, the economics here are driving the move from traditional

to cloud. They're also looking to get off of dated software and hardware

infrastructure. A lot of people are running old hardware, it's not that

efficient, can be costly to maintain and in some cases, difficult or

impossible, to replace. There is a tie at 50 percent each in concern about

the total cost of ownership, probably trying to get that down, and a

desire to consolidate and integrate more apps and data, so seeking a

transformation of their apps and data.

Coming up on the lower end of their motivations are complexity and

support difficulties, and the developer preference for cloud models. So,

the economics are driving this shift. That should come as no surprise,

Tim, that a lot of people are under pressure to do more with less and to

modernize at the same time. The proverbial changing of the wings of the

airplane while keeping it flying. Is there any more you would offer

in terms of the economic drivers for why people should consider going from

a traditional data center to a hybrid IT environment?

Crawford: It's not surprising, and the reason I say that is this economic

upheaval actually started about 10 years ago when we really felt that economic

downturn. It caused a number of organizations to say, "Look, we don't

have the money to be able to upgrade or replace equipment on our regular

cycles."

And

so instead of having a four-year cycle for servers, or a five-year

cycle for storage, or in some cases as much as 10-plus cycle for

network -- they started kicking that can down the road. When the economic

situation improved, rather than put money back into infrastructure, people

started to ask, "Are there other approaches that we can take?"

Now, at the same time, cloud was really beginning to mature and become a viable

solution, especially for mid- to large- enterprises. And so, the combination

of those two opened the door to a different possibility that didn't have

to do with replacing the hardware in corporate data centers.

Instead of having a four-year cycle for servers or five-year cycle for storage, they started kicking the can down the road.

And then you have the third piece to that trifecta, which are the overall

business demands. We saw a very significant change in customer buying

behavior at the same time, which is people were looking for things now.

We saw the uptick of Amazon use and away

from traditional retail, and that trend really kicked into gear around

the same time. All of these together lead into this shift to demand

for a different kind of model, looking at OpEx versus CapEx.

Gardner: Dave, you and I have talked about this a lot over the past

10 years, economics being a driver. But you don't necessarily always save

money by going to cloud. To me, what I see in these results is not

just seeking lower total cost -- but simplification, consolidation and

rationalization for what enterprises do spend on IT. Does that make sense

and is that reflected in your practice?

Savings, strategy and speed

Linthicum: Yes, it is, and I think that the primary reason for moving to

the cloud has morphed in the last five years from the CapEx saving money, operational

savings model into the need for strategic value. That means gaining agility,

ability to scale your systems up as you need to, to adjust to the needs of

the business in the quickest way -- and be able to keep up with the speed

of change.

A lot of the Global

2,000 companies out there are

having trouble maintaining change within the organization, to keep up with

change in their markets. I think that's really going to be the death of a

thousand cuts if they don't fix it. They're seeing cloud as an enabling

technology to do that.

In other words, with

cloud they can have the resources they need, they can get to the

storage levels they need, they can manage the data that they need -- and

do so at a price point that typically is going to be lower than the

on-premise systems. That's why they're moving in that direction. But like

we said earlier, in doing so they're moving into more complex models.

They're typically going to be spending a bit more money, but the value of

IT -- in its ability to delight the business in terms of new capabilities --

is going to be there. I think that's the core metric we need to consider.

Gardner: David, at Navisite, when it comes to cost balanced by

the business value from IT, how does that play out in a

managed hosting environment? Do you see organizations typically wanting to

stick to what they do best, which is create apps, run business processes,

and do data science, rather than run IT systems in and out of every

refresh cycle? How is this shaking out in the managed services business?

Grimes: That's exactly what I'm seeing. Companies are really

moving toward focusing on their differentiation. Running infrastructure

has become almost like having power delivered to your data center. You

need it, it's part of the business, but it's rarely differentiating. So

that's what we're seeing.

Running

infrastructure has become almost like having power delivered to your

data center. You need it, but its rarely differentiating.

One of the things

in the survey results that does surprise me is the relatively low scoring

for the operations complexity and support difficulties. With the pace of

technology innovation happening, and even within VMware, within the

enterprise context, but certainly within the context of the cloud

platforms, Azure in particular, the skillsets to use those platforms,

manage them effectively and take the biggest advantage of them are in

exceedingly high demand. Many organizations are struggling to acquire

and retain that talent. That's certainly been my experience in with

dealing with my clients and prospects.

Gardner: Now that we know why people want to move, let's look

at what it is that's preventing them from moving. What are the chief obstacles that

are preventing those in our audience from moving off of a legacy environment

like VMware?

There's more than just a technological decision here. Dell Technologies is the major controller of VMware, even with VMware being a

publicly traded company. But Dell Technologies, in order to go private,

had to incur enormous debt, still in the vicinity of $48 billion. There's

been reports recently of a reverse merger, where VMware as a public

company will take over Dell as a private company. The markets didn't necessarily go for that, and it creates a bit of confusion and concern in the

market. So Dave, is this something IT operators and architects should concern

themselves with when they're thinking about which direction to go?

Linthicum: Ultimately, we need to look at the health of the company

we're buying hardware and software from in terms of their ability to be

around over the next few years. The reality is that VMware, Dell, and

[earlier Dell merger target] EMC are mega forces in terms of a legacy footprint in a majority

of data centers. I really don't see any need to be concerned about the

viability of that technology. And when I look at viability of companies, I

look at the viability of the technology, which can be bought and sold, and

the intellectual property can be traded off to other companies. I don't

think the technology is going to go away, it's just too much of a

cash cow. And the reality is, whoever owns VMware is going to be able to

make a lot of money for a long period of time.

Gardner: Tim, should organizations be concerned in that they

want to have independence as VMware customers and not get locked in to

a hardware vendor or a storage vendor at the same time? Is there

concern about VMware becoming too tightly controlled by Dell at some

point?

Partnership prowess

Crawford: You always have to think about who it is that you're

partnering with. These days when you make a purchase as an

IT organization, you're really buying into a partnership, so you're buying

into the vision and direction of that given company.

And I agree with

Dave about Dell, EMC, and VMware in that they're going to be around for a

long period of time. I don't think that's really the factor to be

as concerned with. I think you have to look beyond that.

You have to look at

what it is that your business needs, and how does that start to influence

changes that you make organizationally in terms of where you focus your

management and your staff. That means moving up the chain, if you

will, and away from the underlying infrastructure and into applications

and things closely tied to business advantage.

As you start to do

that, you start to look at other opportunities beyond just virtualization.

You start breaking down the silos, you start breaking down the components

into smaller and smaller components -- and you look at the different

modes of system delivery. That's really where cloud starts to play a role.

Gardner: Let's look now to our audience for what they see as

important. What are the chief obstacles preventing you from moving off of

a legacy virtualization environment? Again, the economics are quite

prevalent in their responses.

By a majority,

they are not sure that there's sufficient return on investment (ROI) benefits.

They might be wondering why they should move at all. Their fear of a

lock-in to a primary cloud model is also a concern. So, the economics

and lock-in risk are high, not just from being stuck on a virtualization

legacy -- but also concern about moving forward. Maybe they're like the

deer in the headlights.

You

have to look at what it is that your business needs, and how does that

start to influence changes that you make organizationally, of where you

focus your management and your staff.

The third concern,

a close tie, are issues around compliance, security, and regulatory

restrictions from moving to the cloud. Complexity and uncertainty that the

migration process will be successful, are also of concern.

They're worried about that lift and shift process.

They are less

concerned about lack of support for moving from the C-Suite or business

leadership, of not getting buy-in from the top. So … If it's working,

don't fix it, I suppose, or at least don't break it. And the last issue of

concern, very low, is that it’s still too soon to know which cloud choices

are best.

So, it's not that they don't understand what's going on with

cloud, they're concerned about risk, and complexity of staying is a

concern -- but complexity of moving is nearly as big of a concern. David,

anything in these results that jump out to you?

Feel the fear and migrate anyway

Grimes: Of those not being sure of the ROI benefits, that's been a

common thread for quite some time in terms of looking at these cloud migrations.

But in our experience, what I've seen are clients choosing to move to a VMware cloud hosted by Navisite. They ultimately end up unlocking

the business agility of their cloud, even if they weren't 100 percent sure

going into it that they would be able to.

But time and time

again, moving away from the enterprise data center, repurposing the spend

on IT resources to become more valuable to the business -- as opposed to

the traditional keeping the lights on function -- has played out on a

fairly regular basis.

I agree with the audience and the response here around the fear of lock-in. And

it's not just lock-in from a basic deployment infrastructure perspective,

it's fear of lock-in if you choose to take advantage of a cloud’s higher-level

services, such as data analytics or all the different business things that

are now as-a-service. If you buy into them, you certainly increase

your ability to deliver. Your own pace of innovation can go through the

roof -- but you're often then somewhat locked in.

You're buying into a particular service model, a set of APIs,

et cetera. It's a form of lock-in. It is avoidable if you want to

build in layers of abstraction, but it's not necessarily the end of the

world either. As with everything, there are trade-offs. You're getting a lot of

business value in your own ability to innovate and deliver quickly, yes, but

it comes at the cost of some lock-in to a particular platform.

Gardner: Dave, what I'm seeing here is people explaining why hybrid

is important to them, that they want to hedge their bets. All or

nothing is too risky. Does that make sense to you, that what these results

are telling us is that hybrid is the best model because you can spread

that risk around?

IT in the balance between past and future

Linthicum: Yes, I think it does say that. I live this on a daily

basis in terms of ROI benefits and concern about not having enough, and

also the lock-in model. And the reality is that when you get to an

as-is architecture state, it's going to be a variety -- as we mentioned

earlier – of resources that we're going to leverage.

So, this is not

all about taking traditional systems – and the application workloads

around traditional systems -- and then moving them into the cloud and

shutting down the traditional systems. That won't work. This is about a

balance or modernization of technology. And if you look at that, all bets

are on the table -- including traditional, including private cloud,

and public cloud, and hybrid-based computing. Typically, it's going to be

the best path to success at looking at all of that. But like I said, the

solution's really going to be dependent on the requirements on the

business and what we're looking at.

Going forward, these kinds of decisions are falling into a pattern, and I

think that we're seeing that this is not necessarily going to be pure-cloud

play. This is not necessarily going to be pure traditional play, or pure

private cloud play. This is going to be a complex architecture that

deals with a private and public cloud paired with traditional systems.

And so, people who do want to hedge their bets will do that

around making the right decisions that they leverage the right resources

for the appropriate task at hand. I think that's going to be the winning

end-point. It's not necessarily moving to the platforms that we think are cool,

or that we think can make us more money -- it's about localization of the

workloads on the right platforms, to gain the right fit.

Gardner: From the last two survey result sets, it appears incumbent

on legacy providers like VMware to try to get people to stay on their designated

platform path. But at the same time, because of this inertia to shift, because

of these many concerns, the hyperscalers like Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and Amazon Web Services also need to sweeten their deals. What are

these other cloud providers doing, David, when it comes to trying to

assuage the enterprise concerns of moving wholesale to the cloud?

It's

not moving to the platforms that we think are cool, or that can make us

money, it's about localization of the workloads on the right platforms,

to get the right fit.

Grimes: There are certainly those hyperscale players, but there are

also a number of regional public cloud players in the form of the VMware partner ecosystem.

And I think when we talk about public versus private, we also need to make

a distinction between public hyperscale and public cloud that still could be

VMware-based.

I think one interesting thing that ties back to my earlier comments

is when you look at Microsoft Azure and their Azure Stack hybrid cloud strategy.

If you flip that 180 degrees, and consider the VMware on AWS strategy, I

think we'll continue to see that type of thing play out going forward.

Both of those approaches actually reflect the need to be able to

deliver the legacy enterprise workload in a way that is adjacent from

an equivalence of technology as well as a latency perspective. Because one

thing that's often overlooked is the need to examine the hybrid cloud

deployment models via the acceptable latency between applications that

are inherently integrated. That can often be a deal-breaker for a

successful implementation.

What we'll see is this continued evolution of ensuring that we can solve

what I see as a decade-forward problem. And that is, as organizations

continue to reinvent their applications portfolio they must also evolve

the way that they actually build and deliver applications while continuing

to be able to operate their business based on the legacy stack that's

driving day-to-day operations.

Moving solutions

Gardner: Our final survey question asks What are your current plans

for moving apps and data from a legacy environment like VMware, from a

traditional data center?

And two strong answers

out of the offerings come out on top. Public clouds such as Microsoft

Azure and Google Cloud, and a hybrid or multi-cloud approach. So again,

they're looking at the public clouds as a way to get off of their

traditional -- but they're looking not for just one or a lock-in, but

they're looking at a hybrid or multi-cloud approach.

Coming up zero, surprisingly,

is VMware on AWS, which you just mentioned, David. Private cloud

hosted and private cloud on-premises both come up at about 25 percent, along

with no plans to move. So, staying on-premises in a private cloud has traction

for some, but for those that want to move to the dominant hyperscalers,

a multi-cloud approach is clearly the favorite.

Linthicum: I thought there would be a few that would pick VMware on AWS,

but it looks like the audience doesn't necessarily see that that's going

to be the solution. Everything else is not surprising. It's aligned with

what we see in the marketplace right now. Public cloud movement to Azure,

Google Cloud and then also the movement to complex clouds like hybrid and

multi-cloud also seem to be the two trends worth seeing right now in

the space, and this is reflective of that.

Gardner: Let's move our discussion on. It's time to define the right

trade-offs and rationale when we think about these taxing choices. We know

that people want to improve, they don't want to be locked in, they want

good economics, and they're probably looking for a long-term

solution.

Now that we've

mentioned it several times, what is it about Azure and Azure Stack that

provides appeal? Microsoft’s cloud model seems to be differentiated in

the market, by offering both a public cloud component as well as an

integrated – or adjacent -- private cloud component. There’s a path for

people to come onto those from a variety of different deployment histories

including, of course, a Microsoft environment -- but also a VMware

environment. What should organizations be thinking about, what are the proper

trade-offs, and what are the major concerns when it comes to picking the

right hybrid and multi-cloud approach?

Strategic steps on the journey

Grimes: At the end of the day, it's ultimately a journey and that

journey requires a lot of strategy upfront. It requires a lot of planning,

and it requires selecting the right partner to help you through that

journey.

Because whether

you're planning an all-in on Azure, or an all-in on Google Cloud, or you

want to stay on VMware but get out of the enterprise data center, as

Dave has mentioned, the reality is everything is much more complex than it

seems. And to maximize the value of the models and capabilities that are

available today, you're almost necessarily going to end up in a hybrid

deployment model -- and that means you're going to have a mix of

technologies in play, a mix of skillsets required to support them.

Whether

you're planning on an all-Azure or all-Google, or you want to stay on

VMware, it's about getting out of the enterprise datacenter, and the

reality is far more complex than it seems.

And so I think one of the key things that folks should do is

consider carefully how they partner regardless of where they are in that

journey, if they are on step one or step three, to continue that journey

is going to be critical on selecting the right partner to help them.

Gardner: Dave, when you're looking at risk versus reward, cost versus

benefits, when you're wanting to hedge bets, what is it about Microsoft

Azure and Azure Stack in particular that help solve that? It seems to me

that they've gone to great pains to anticipate the state of the market

right now and to try to differentiate themselves. Is there something

about the Microsoft approach that is, in fact, differentiated among the

hyperscalers?

A seamless secret

Linthicum: The paired private and public cloud, with

similar infrastructures and similar migration paths, and dynamic migration

paths, meaning it could be workloads in between them -- at least this is

the way that it's been described -- is going to be unique in the market. Kind

of the dirty little secret.

It's going to be

very difficult to port from a private cloud to a public cloud because

most private clouds are typically not AWS and not Google, and they don't

make private clouds. Therefore, you have to port your code between the two,

just like you've had to port systems in the past. And the normal issues

about refactoring and retesting, and all the other things, really come home to

roost.

But Microsoft

could have a product that provides a bit more of a seamless capability

of doing that. And the great thing about that is I can really localize on

whatever particular platform I'm looking at. And if I, for example, “mis-localize”

or I misfit, then it's a relatively easy thing to move it from private to

public or public to private. And this may be at a time where the market

needs something like that, and I think that's what is unique about it in

the space.

Gardner: Tim, what do you see as some of the trade-offs, and what

is it about a public, private hybrid cloud that's architected to be just

that -- that seemingly Microsoft has developed? Is that differentiating,

or should people be thinking about this in a different way?

Crawford: I actually think it's significantly differentiating,

especially when you consider the complexity that exists within the mass of

the enterprise. You have different needs, and not all of those needs can

be serviced by public cloud, not all of those needs can be serviced by

private cloud.

There's a model

that I use with clients to go through this, and it's something that I

used when I led IT organizations. When you start to pick apart these

pieces, you start to realize that some of your components are well-suited

for software as a service (SaaS)-based alternatives, some of the

components and applications and workloads are well-suited for public

cloud, some are well-suited for private cloud.

A good example of that is if you have sovereignty issues, or compliance and

regulatory issues. And then you'll have some applications that just aren't

ready for cloud. You've mentioned lift and shift a number of times, and

for those that have been down that path of lift and shift, they've also

gotten burnt by that, too, in a number of ways.

And so, you have to be mindful of what applications go in

what mode, and I think the fact that you have a product like Azure Stack

and Azure being similar, that actually plays pretty well for an enterprise

that's thinking about skillsets, thinking about your development cycles,

thinking about architectures and not having to create, as Dave

was mentioning, one for private cloud and a completely different

one for public cloud. And if you get to a point where you want to move

an application or workload, then you're having to completely redo it over

again. So, I think that Microsoft combination is pretty unique, and will

be really interesting for the average enterprise.

Gardner: From the managed service provider (MSP) perspective, at

Navisite you have a large and established hosted VMware business, and you’re

helping people transition and migrate. But you're also looking at the

potential market opportunity for an Azure Stack and a hosted Azure Stack

business. What is it for the managed hosting provider that might make

Microsoft's approach differentiated?

A full-spectrum solution

Grimes: It comes down to what both Dave and Tim mentioned. Having a

light stack and being able to be deployed in a private capacity,

which also -- by the way -- affords the ability to use bare metal

adjacency, is appealing. We haven't talked a lot about bare metal, but it is something

that we see in practice quite often. There are bare metal workloads that need

to be very adjacent, i.e. land adjacent, to the virtualization-friendly

workloads.

Being able

to have the combination of all three of those things is what makes AzureStack attractive to a hosting provider such as Navisite. With it, we can

solve the full-spectrum of the needs of the client, covering bare metal,

private cloud, and hyperscale public -- and really in a seamless way --

which is the key point.

Gardner: It's not often you can be as many things to as many people as

that given the heterogeneity of things over the past and the difficult

choices of the present.

We have been

talking about these many cloud choices in the abstract. Let's now go to a

concrete example. There's an organization called Ceridian. Tell us about how they solved their requirements problems?

Azure

Stack is attractive to a hosting provider like Navisite. With it we can

solve the full-spectrum of the needs of the client in a seamless way.

Grimes: Ceridian is a global human capital management

company, global being a key point. They are growing like gangbusters and

have been with Navisite for quite some time. It's been a very long

journey.

But one thing

about Ceridian is they have had a cloud-first strategy. They embraced

the cloud very early. A lot of those barriers to entry that we saw,

and have seen over the years, they looked at as opportunity, which

I find very interesting.

Requirements around security and compliance are critical

to them, but they also recognized that a SaaS provider that does a very

small set of IT services -- delivering managed infrastructure with

security and compliance -- is actually likely to be able to do that at

least as effectively, if not more effectively, than doing it in-house, and

at a competitive and compelling price point as well.

So some of their challenges really were around all the reasons that

we see, that we talked about here today, and see as the drivers to

adopting cloud. It's about enabling business agility. With the growth that

they've experienced, they've needed to be able to react quickly and deploy

quickly, and to leverage all the things that virtualization and now cloud

enable for the enterprises. But again, as I mentioned before, they worked

closely with a partner to maximize the value of the technologies and

ensure that we're meeting their security and compliance needs and

delivering everything from a managed infrastructure perspective.

Overcoming geographical barriers

One of the core challenges that they had with that growth was

a need to expand into geographies where we don't currently operate

our hosting facilities, so Navisite's hosting capabilities. In

particular, they needed to expand into Australia. And so, what we were

able to do through our partnership with Microsoft was basically deliver to

them the managed infrastructure in a similar way.

This is actually

an interesting use case in that they're running VMware-based cloud in our

data center, but we were able to expand them into a managed Azure-delivered

cloud locally out of Australia. Of course, one thing we didn't touch on

today -- but is a driver in many of these decisions for global

organizations -- is a lot of the data sovereignty and locality regulations are

becoming increasingly important. Certainly, Microsoft is expanding the

Azure platform. And so their presence in Australia has enabled us to

deliver that for Ceridian.

As I think about the key takeaways and learnings from this

particular example, Ceridian had a very clear, very well thought out

cloud-centric and cloud-first strategy. You, Dana, mentioned it earlier, that that

really enables them to continue to keep their focus on the applications

because that's their bread and butter, that's how they differentiate.

By partnering, they're able to not worry about the keeping

the lights on and instead focus on the application. Second, of course, is

they're a global organization and so they have global delivery needs based

on data sovereignty regulations. And third, and I'd say probably most

important, is they selected a partner that was able to bring to bear the

expertise and skillsets that are difficult for enterprises to recruit and

retain. As a result, they were able to take advantage of the different

infrastructure models that we're delivering for them to support their

business.

Gardner: We're now going to go to our question and answer portion.

Kristen Allen of Navisite is moderating our Q and A section.

Bare metal and beyond

Kristen Allen: We have some very interesting questions. The first one ties into

a conversation you were just having, "What are the ROI benefits to moving

to bare metal servers for certain workloads?"

Grimes: Not all software licensing is yet virtualization-friendly, or

at least on a virtualization platform-agnostic platform, and so there's

really two things that play into the selection of bare metal, at least in

my experience. There is kind of a model of bare metal computing,

small cartridge-based computers, that are very specific to certain

workloads. But when we talk in more general terms for a typical

enterprise workload, it really revolves around either software licensing

incompatibility with some of the cloud deployment models or a belief that

there is a performance that requires bare metal, though in practice I

think that's more of optics than reality. But those are the two things

that typically drive bare metal adoption in my experience.

Linthicum: Ultimately, people want access directly for at the

end-of-the-line platforms, and if there's some performance reason, or

some security reason, or some kind of a direct access to some of the input-output

systems, we do see these kinds of one-offs for bare metal. I call them special

needs applications. I don't see it as something that's going to be widely

adopted, but from time to time, it's needed, and the capabilities are

there depending on where you want to run it.

Allen: Our next question is, "Should there be different thinking

for data workloads versus apps ones, and how should they be best integrated

in a hybrid environment?"

The

compute aspect and data aspect of an application should be decoupled.

If you want to you can then assemble them on different platforms, even

one on public cloud and one on private cloud.

Linthicum: Ultimately, the compute aspect of an application and the

data aspect of that application really should be decoupled. Then, if you

want to, you can assemble them on different platforms. I would typically

think that we're going to place them either on all public or all private,

but you can certainly do one on private and one on public, and one on

public and one on private, and link them that way.

As we're migrating

forward, the workloads are getting even more complex. And there's some

application workloads that I've seen, that I've developed, where the

database would be partitioned against the private cloud and the public

cloud for disaster recovery (DR) purposes or performance purposes, and things

like that. So, it's really up to you as the architect as

to where you're going to place the data in adjacent relation to the

workload. Typically, a good idea to place them as close to each other as

they can so they have the highest bandwidth to communicate to each other.

However, it's not necessary depending on what the application's doing.

Gardner: David, maybe organizations need to place their data in a certain

jurisdiction but might want to run their apps out of a data center

somewhere else for performance and economics?

Grimes: The data sovereignty requirement is something that we touched on

and that's becoming increasingly important and increasingly, that's a

driver too, in deciding where to place the data.

Just following on

Dave's comments, I agree 100 percent. If you have the opportunity to

architect a new application, I think there's some really interesting

choices that can be made around data placement, network placement,

and decoupling them is absolutely the right strategy.

I think the challenge

many organizations face is having that mandate to close down the

enterprise data center and move to the "cloud." Of course, we

know that “cloud” means a lot of different things but, do that in a legacy application

environment and that will present some unique challenges as well, in terms

of actually being able to sufficiently decouple data and applications.

Curious, Dave,

if you've had any successes in kind of meeting that challenge?

Linthicum: Yes. It depends on the application workload and how flexible the

applications are and how the information is communicating between the

systems; also security requirements. So, it's one of those

obnoxious consulting responses, “it depends” as to whether or not we can

make that work. But the thing is the architecture is a legitimate

architectural pattern that I've seen before and we've used it.

Allen: Okay. How do you meet and adapt for Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) requirements

and still maintain stable connectivity for the small business?

Grimes: HIPAA, like many of the governance programs, is a very large and

co-owned responsibility. I think from our perspective at Navisite, part of

Spectrum Enterprise, we have the unique capability of delivering both the

network services and the cloud services in an integrated way that can

address the particular question around stable connectivity. But

ultimately, HIPAA is a blended responsibility model where the infrastructure

provider, the network provider, the provider managing up to whatever layer

of the application stack will have certain obligations. But then the

partner, the client would also retain some obligations as well.

You may also be

interested in: